The only one who might have seen it coming was the dam keeper, Tony Harnischfeger. On the morning of March 12, 1928, he had spotted leaks forming along the abutments and noticed that the water looked “dirty,” likely indicating that foundation material was spilling out from beneath the structure.

Engineer William Mulholland inspected the dam himself and declared it sound.

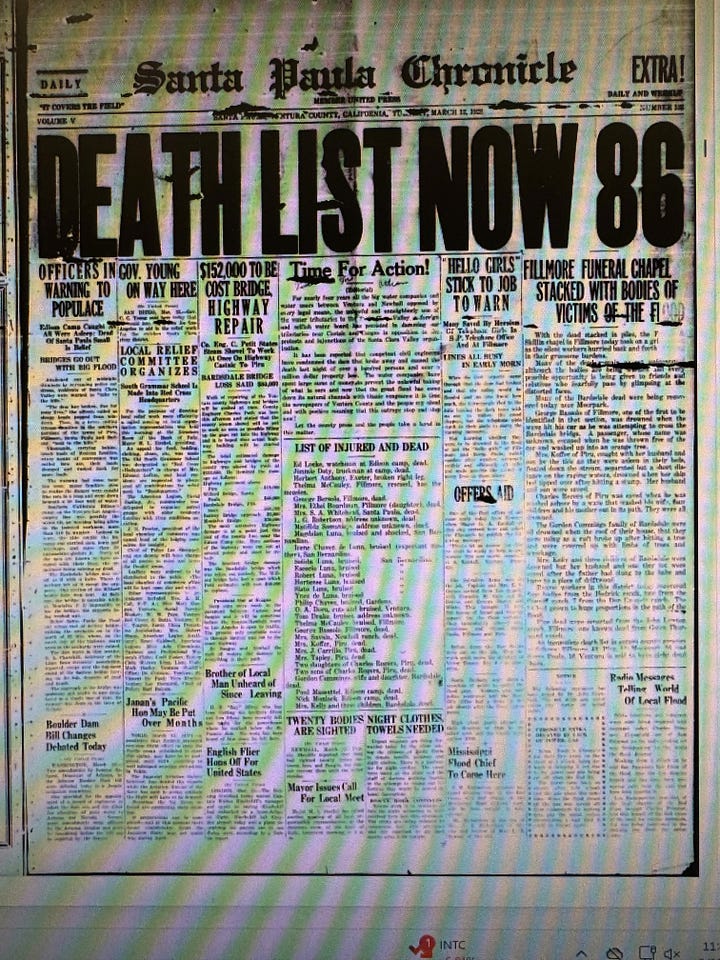

No one else was any wiser. That day, the Santa Paula Chronicle was promoting its free new cooking class. The Showdown starring George Bancroft was set to open at the Glen City theater, and the Teapot Dome scandal was roiling national politics.

As far as the residents of the Santa Clara River Valley were concerned, the only telltale sign of imminent disaster that night of March 12 was the brief flickering of lights moments before the dam erupted.

Just before midnight, William Mulholland’s grand vision for a water reservoir that would serve the Los Angeles basin collapsed, unleashing 12.4 billion gallons of water that would hurtle through San Francisquito Canyon, rush through the town of Castaic and follow both gravity and topography across some 54 miles—the entire length of the Santa Clara River Valley—until the torrent crashed into the ocean.

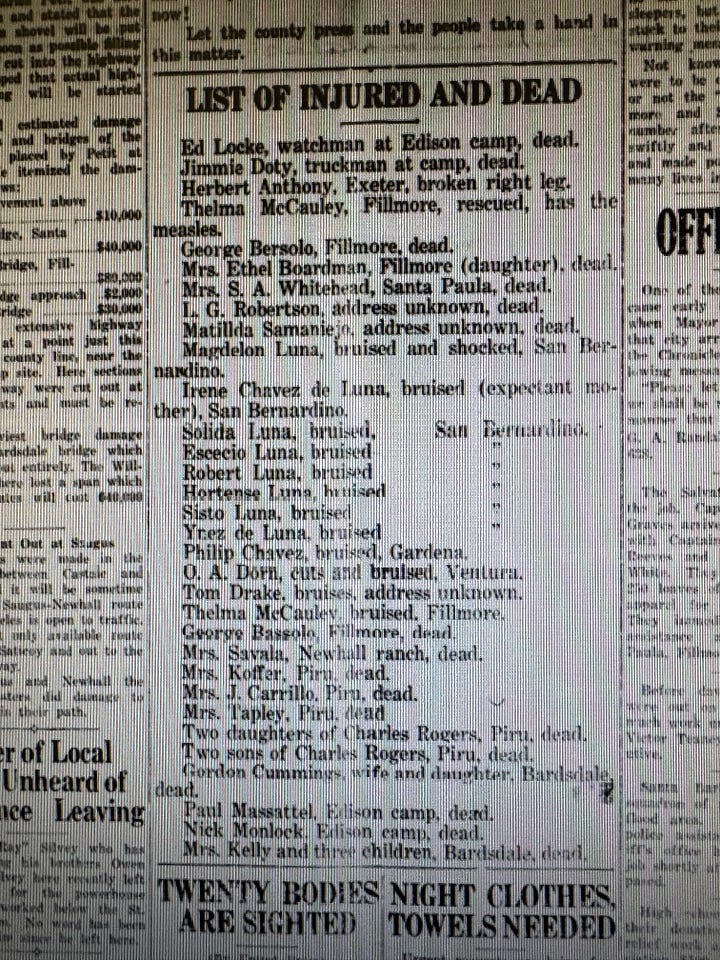

The disaster damaged more than a thousand homes, destroyed 909. It claimed at least 450 lives, but the true number may never be known, as several bodies had washed out to sea, never to be recovered. Dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger and his six-year-old son would be the first such first victims. The flood waters devastated thousands of dollars’ worth of agricultural land. Residents had little time to get to safety—many wound up seeking higher ground on their roofs or trying to surf wayward mattresses through the raging waters. One wrong turn, one wrong decision—Go out this door or that one?—could mean the difference between surviving the flood or drowning in it.

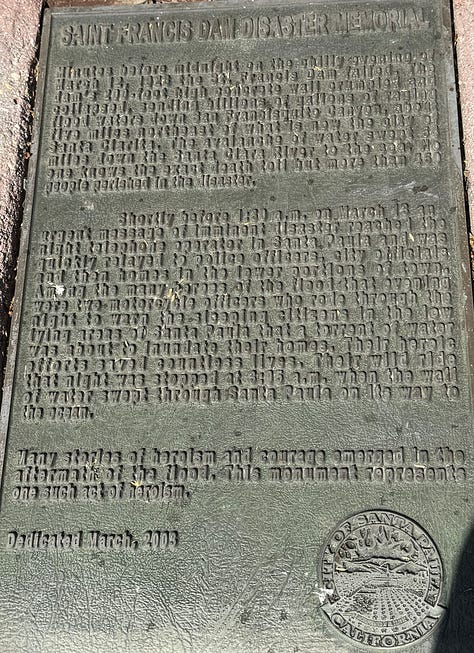

The disaster has since left its mark on the valley and on the lives of those who lived to tell the tale. In 2003, Santa Paula marked the 75th anniversary of the collapse. A memorial to the officers who embarked on a modern “Paul Revere”-style ride through Santa Paula to warn residents of the coming danger now stands near the train depot at Santa Barbara and 10th Streets.

The dam’s failure likely resulted from a combination of factors, not the least of which were the instability of the land it was anchored to (little was known at the time about the importance of geology) and plain old human hubris. It was thought that Mulholland may have encouraged his engineers to build the dam taller than the original specs, without increasing the thickness of the walls in proportion—and thus failing to account for the increased force of water the walls would have to retain.

Mulholland took full responsibility for the disaster and retired later that year.

His work as L.A.’s first water chief, as well as his engineering triumphs, ensured L.A.’s viability as a growing metropolis but would spark water wars throughout the state. Those wars, and his legendary character, were the inspiration for the 1974 film, Chinatown.

Stay tuned in the coming weeks for further articles about the disaster, its survivors, and its angels and miracle workers.

References:

Santa Paula Chronicle, with thanks to Blanchard Library and the “California Room”

Lost L.A., Season 7, Episode 3: “When the St. Francis Dam Collapsed”

Images of America: St. Francis Dam Disaster by John Nichols. ©2002

The St. Francis Dam Disaster Revisited by the Historical Society of Southern California. ©1995

Santa Paula Times Archives, “The Warning: Memorial of St. Francis Dam Disaster placed,” March 7, 2003

Wikipedia, “St. Francis Dam”